Paging Dr. Christaller

.

Origin of an Idea

Origin of an Idea.

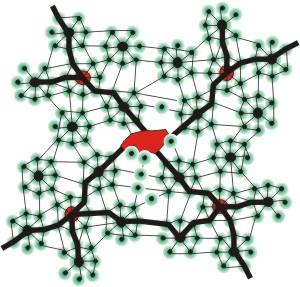

Briefly, Walter Christaller was a German Geographer that postulated in his 1933 doctoral essay that market-based forces inevitably created a hierarchical arrangement of towns and cities. In any given area, a large number of small communities would surround a smaller number of towns and even fewer large cities. The physical layout would roughly be approximated as so:

.

http://www.csiss.org/classics/uploads/pa_centralplace.gif

.

To make the theory work, Christaller had to assume the following factors:

.

* The area was flat without any geological barriers.

* The population was an evenly distributed

* All natural resources were evenly distributed

* All consumers maintained the same purchasing power

* No provider of goods or services could earn excessive profits

* Only one type of transport existed and it would be equally accessible in all directions

.

It was a good start. But a stronger force loomed.

Globalism and the Rise of the MegaCities

.

.

The result of these trends is a global settlement pattern that now concentrates most people in major metropolitan regions and MegaCities. This growth in mass-urbanization of course was made possible by an abundant and inexpensive supply of energy, which subsidized the increasing costs of constructing and maintaining ever larger settlements. As time progressed, the benefits—and costs—of maintaining this arrangement were spread far and wide until most people’s comfort, livelihood and in many cases, existence were being subsidized by labor, money or resources from somewhere else.

.

The Death of Globalism and the Resurrection of Christaller

.

While Walter Christaller’s theory remained largely academic over the intervening decades (most people probably have never heard of him), the concept of place hierarchy did become important to the marketing and retail sectors, which partially goes to explain how and where business decide to site and expand operations.

.

Globalism is of course, highly dependent on the continuation of cheap energy. Once that supply has been consumed however, the whole economic arrangement of today will be turned on its head. No longer will it make sense to mass produce in select locations for global distribution. A new framework will have to be established.

.

In previous postings here and elsewhere on the Internet, the concept of a (much smaller) community-based existence is often suggested. While this makes for a very strong starting point for coping with peak energy, it too often ignores the community’s place in the greater world. No man is an island and nor should a community be one either. Unless an area is truly isolated or incredibly blessed with resources, trade is inevitable. As we move into an energy-poor future, we need a geographical pattern that minimizes travel and maximizes efficiency.

.

This is where Christaller comes in. The same hierarchical arrangement of settlement patterns first observed of Southern Bavaria or the Midwestern US should become the basis for all human settlement. But rather than simply explaining historical development patterns, Central Place Theory could be modified as to guide future settlement patterns and linkages.

.

Developing a New Concept of Central Place

.

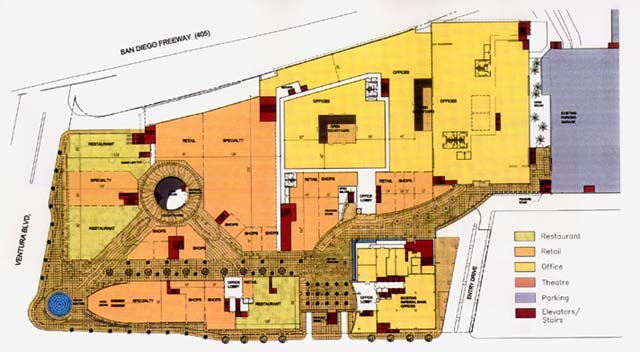

Linkage—or the relationship between places—is key to a revised Central Place Theory. Each place from the smallest community to the largest city within an area is to be linked to one another. These links would be physical (roads or rails), resource driven (availability of food, raw materials), economic (trade) and administrative. What each community would produce and ultimately transport would be determined by the community’s size and its neighbors. Similarly, the question how these communities would be physically linked is also important. The issue of transportation is a direct part of the equation. Ideally, distances would remain shortest for the most frequently transported or bulky items. This way, simple road ways could permit anything from pedestrian and pedal-powered vehicles to busses and trucks. These vehicles could take care of most transportation needs in and around an average community. With small distances between settlements, even bicycle and pedestrian trips between towns would be plausible. The remaining goods could be shipped on trucks. As the distances increase, direct (and frequent) travel between communities would decrease. In effect, the strength of the linkage between any two given places would only be as good the relationship between each place, which is directly related to the distance and ease of travel.

.

Putting this theory into practice would be difficult, but doable in a number of regions. Re-establishing linkages in areas where it was lost and artificially creating them elsewhere will be of top importance. So will the initiation of countless new small communities in the midst of what was once “productive” farmland. In a number of cases, the shells of these communities already exist in the form of dying or abandoned towns. In other locations, new settlements would have to be formed from scratch.

.

The reason for doing this is that as it has been frequently discussed, the small agrarian community ideally should be the basic form of settlement for the majority of the population. The smallest sized communities need to be the most prevalent and be scattered around the country side every few miles at most. Each one would be more than self sufficient in food production, producing a slight surplus that could be exported. Each community would also attempt to produce as many of its essential daily products and ideally generate most of its energy needs for their own consumption. By doing this, the need for a significant amount of trade could be eliminated. Even if each community did not produce everything they needed on a daily basis, the increased amount of local production would still significantly reduce transportation needs. Though a majority of the working aged population will be engaged in production activities of some kind, each community would maintain a few individuals in the other professions such as retail, security, health care, education and other essential service sector professions.

.

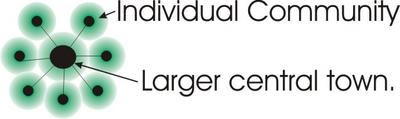

Each of these small settlements, which would ideally range in size from several hundred to just over a thousand inhabitants, would surround a larger city. Ideally these settlements would be close by, no more than a mile or two, to facilitate easy travel between the small community and the larger town. If fixed rail service was an option, a single stop could serve an entire small community (due to the small geographic spread) and most of the larger town. Otherwise bus service would suffice along with the bicyclists and horse carts.

.

The larger town itself would ideally be the home of several thousand individuals and house some of the higher level industries and functions that would not make much sense to replicate in each of the smaller communities. This larger town would also produce most of its required food locally but if it were forced to, could close any shortfall in local production by importing from its surrounding communities.

The larger town itself would ideally be the home of several thousand individuals and house some of the higher level industries and functions that would not make much sense to replicate in each of the smaller communities. This larger town would also produce most of its required food locally but if it were forced to, could close any shortfall in local production by importing from its surrounding communities..

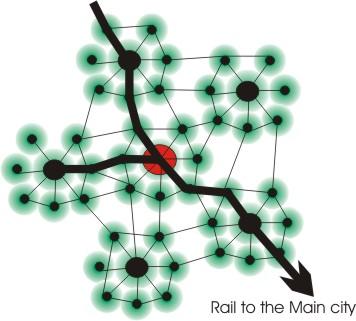

These towns would orbit a larger city, which would maintain higher levels of population and job specialization than the surrounding towns and communities. Connections between the smaller towns and the larger city would ideally be made by rail, which would allow the easy transportation of goods and people between places. Frequent bus service could suffice if rail transit was impossibility. With a vast majority of the population residing within walking distance, this would make a lot of sense. Distances between the smaller towns and the city would vary, but would inevitably be situated further away than the small communities were located. These cities themselves would be immediately surrounded by small agricultural communities, with some urban agriculture occurring within the city limits. However, due to the numbers of individuals not engaged in agriculture in each of these cities, food would most likely have to be imported from slightly further a field. Fortunately those import sources would originate from the surrounding towns and communities at distance of no more than 50 miles.

.

Finally these cities would “orbit” an administrative capital of sorts. This capital city would be the administrative hub for this region and carry out top level governance. However, due to the numerous smaller and mostly self-sufficient settlements, governance could be smaller and more nimble than today’s bloated bureaucracies. Additionally this top level city would house the most technologically sophisticated industries as well as perform or produce those products needed in small quantities as well as serve as the region’s educational and cultural center (home to a college and a performing arts contingent.)

Finally these cities would “orbit” an administrative capital of sorts. This capital city would be the administrative hub for this region and carry out top level governance. However, due to the numerous smaller and mostly self-sufficient settlements, governance could be smaller and more nimble than today’s bloated bureaucracies. Additionally this top level city would house the most technologically sophisticated industries as well as perform or produce those products needed in small quantities as well as serve as the region’s educational and cultural center (home to a college and a performing arts contingent.).

Ideally the region, taken as a whole should be self-sufficient. Its borders would correspond to natural geographical boundaries; in essence a bio-region. Trade could still occur, but it would not be necessary for survival. The size of the bio-region would be ideally related to the underlying carrying capacity and serve as the ultimate determination of how many people could it support.

.

Restating Central Place for a Low Energy World.

.

Unlike Christaller, the settlements need not be geometrically ordered. In all likelihood, hierarchical clustering may prove to be a better arrangement. Maximizing activities in smaller areas is an effective way to reduce overall impacts.

.

So would creating a hierarchical framework. Unlike Christaller, this plan of action implies actively:

.

* Identifying an area of common geographical and geological features (a bio-region)

* Redistributing population from densely populated cities to lesser populated countryside.

* Producing as much natural resource as needed on a local basis and evenly distributing the rest.

* Ensuring all consumers have equal access to the economy.

* Protecting against excessive production of goods or services for outside export or excessive profiteering.

* Trying to reduce all needs for travel while expanding mass transit options.

.

It does not matter what the actual geographic layout is like, the important part of the new conceptual framework is the relational structure.

.

Such a plan of action would no doubt be controversial.

.

This concept of course is only theoretical. Implementation would be another story and not in the scope discussion at this time. The key point that I was trying to make here is that Central Place Theory as modified could provide a framework of geographical organization of land uses and settlement patterns that could make any post fossil-fuel era existence eminently more survivable, sustainable and perhaps even…pleasant.